Maternal Malnutrition Might Occur as a Result of Morning Sickness when Left Unresolved Maternal Malnutrition Might Occur as a Result of Morning Sickness when Left Unresolved Life is a cycle. Things branded as conventional and traditional are making a comeback these days in full swing. Bell bottom pants, tie-dye prints, puff sleeves, mini dresses from the 60s and maxi dresses from the 70s have captured the attention of fashionistas. In the food sector too while we gloat about superfoods and supplements more and more individuals are interested in knowing more about grandma recipes and authentic plant-based foods that ruled our country once. The present world boasts of organic foods, nutrient-packed foods such as kale and sea weeds and protein shakes that add energy to our body. Despite advancements the heath of this generation is only deteriorating at a faster pace. While youngsters in their 20s and 30s complain of knee pain our grandparents are hale and healthy even in their 70s and 80s. They were brought up in a processed food-free world where all the ingredients were pure, pesticide-free and healthy. They relied on millets, natural produce and above all toiled through the day to make ends meet unlike the present-day people who sit down in front of a computer and keep hitting the keyboard as fast as possible! Ayurveda is deep-rooted in India and our ancestors relied on this treatment method for curing a number of ailments. Ginger, gooseberry, long pepper and garlic have been indispensable part of our culinary preparations since time immemorial. Do you remember the days when our complains on digestive problems and stomach pain had always been responded with simple yet effective recipes using ginger by our grandma? While it could have sounded funny back then but we still consumed it fearing our mom’s thrashings otherwise they have definitely helped up sail through tough seas quite a lot many times. Maybe now, medically too we are revisiting our traditional recipes for soothing certain ailments and finding relief from our age-old ingredients. With this, there is no denial in accepting the fact that ginger occupies one of the primary positions in all our homes. We might use it for preparing masala tea, as a spice in making sabjis, its juice is consumed to relieve digestive problems and we sometimes eat small chunks of ginger with jaggery to avoid vomiting. Overeating can sometimes lead to a persistent vomiting sensation that’s otherwise not much of a problem. But vomiting and nausea remain critical factors affecting quality of life in most pregnant women in the form of morning sickness. Ginger, a traditional form of medicine has once again occupied mainstream position in relieving nausea and vomiting symptoms in pregnant women. Traditional & Complementary Medicines (T&CM) The World Health Organization feels that T&CM have come a great way from their origin. The side effects of common medicines and the antibiotic resistance that’s increasing seen these days are evidence enough to make a switch to other forms. Ginger, a herb popular for its culinary and medicinal value has been used in Asian and Ayurvedic medicines as an anti-inflammatory and anti-pyretic agent to treat diabetes, rheumatism, nausea, diarrhoea, stomach pain, UTI, rheumatism and to strengthen memory as well since thousands of years. Though a native of Asia it is now cultivated all around the world making it an indispensable cooking ingredient and a household cure for flatulence. While Indians love this rhizome, even Chinese and Japanese individuals have used it to treat headaches, cold, nausea and stomach problems. Pregnant Chinese women have been consuming ginger to combat morning sickness. Nausea and vomiting are common complaints during the early stages of pregnancy and there are even some theories which support that these symptoms convey the fact that the fetus is healthy and growing normally. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) occur in 80-90% of pregnant women and is known as morning sickness (while it can occur anytime of the day its effects are maximum soon after getting up in most women). It starts by 4-9 weeks of gestation maximizing by 7-12 weeks and subsiding by week 16. Very rarely, some women experience its symptoms (mostly nausea and vomiting, some have nausea without vomiting but vomiting without nausea is a rarity) until delivery. 1-2% women experience a debilitating condition known as ‘Hyperemesis gravidarum’ where nausea and vomiting symptoms are extremely severe that it can lead to starvation and dehydration. Despite these effects the exact cause behind NVP remains a mystery till date. Fighting NVP While we do have traditional medicines to limit NVP many pregnant women prefer not to use them fearing harmful side-effects. While we might argue that NVP is a part and parcel of every pregnancy some women suffer badly from malnourishment, weight loss and a completely undesirable pregnancy phase. Still pharmacological drugs don’t find a place in their kitty and non-pharmacological treatment options are mostly preferred by pregnant women and one such option includes using ginger to treat NVP. Ginger is included in the US Food and Drug Administration’s ‘generally recognised as safe’ list, it is included in the pharmacopoeias of Western countries, the ‘British Herbal Compendium’ lists ginger as a remedy for vomiting with pregnancy and UK has been using ginger capsules as a remedy for motion sickness for more than 40 years. Still, scientific evidence is mixed for using ginger against NVP as higher doses of concentrated ginger in powder form or herbal tinctures increases bleeding risk by decreasing platelet aggregation and also elevates stomach acid production. Below is a systematic review (SR) of the available studies that look into ginger and its effectiveness against NVP. Systematic Review of Ginger as an Aid Against NVP The review included randomized control trials (RCT) where women suffered from NVP. Comparisons were made among women who consumed any form of ginger (fresh root, dried root, powder, tablets, capsules, liquid extract and tea) orally to those on placebo or active ingredient. Databases were searched and the trials were chosen according to the study criteria. Only 12 studies met the study criteria which included a total of 1278 participants. While 11 of the 12 studies included women suffering from NVP only one study included women suffering from HG. Almost all the studies used ginger powder capsules as intervention anywhere between 1000mg and 1950 mg ginger per day. 1 study included ginger biscuits as intervention amounting to 2500 mg ginger per day. One study used ginger syrup, another used ginger extract and yet another used ginger essence. 7 studies used a placebo as control: 2 studies used lactose as placebo, one used lemon oil, one used flour and one used soya bean oil. One study used placebo biscuit and yet another one capsules. Ginger Versus Placebo Seven studies analysed the effect of ginger versus placebo and reported the following results:

Only 3 of 12 studies reported on this. 1 study reported that ginger did not improve response compared to placebo. Adverse Effects & Side Effects Four studies reported no adverse effects of ginger, one study reported that the patient suffered spontaneous abortion while yet another patient sought legal abortion. For any event such as diarrhoea, drowsiness, headache, heartburn, spontaneous abortions and abdominal discomfort that called for medical treatment there was difference seen between the ginger and placebo treatment group. Reduction in Vomiting Frequency 4 studies reported reduction in vomiting episodes but there was no difference in results seen between doses. The reviews do seem to suggest benefits of ginger in minimizing symptoms of nausea in pregnancy but did not have much effect on vomiting episodes. Other Studies Willets et al. conducted a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled study that looked into the effect of ginger extract on morning sickness symptoms in 120 pregnant women. Four days later it was seen that nausea experience score was less than zero but vomiting symptoms were not affected between the ginger-consuming group and the placebo group. Keating et al. showed that 1 g of ginger syrup consumed for two weeks helped 67% women in the ginger group to stop vomiting at day 6 vs 20% in the placebo group. Basirat et al. did a randomized double-blind clinical trial on 62 pregnant women of which 32 women took 5 biscuits daily for 4 days each containing .5 g of ginger. Nausea scores improved in this group compared to placebo but vomiting showed no changes. But 4 days after treatment the number of women who had no vomiting in the ginger group was greater than that in the placebo group. Ding et al. pointed out that the various ginger treatment methods were safe and effective for treating NVP. Two other meta-analyses supported the fact that ginger could be a safe and reliable way to curb nausea and vomiting in pregnant women. Ginger, a herb that’s been in use for centuries is considered to be safe and effective against nausea and vomiting in pregnant women when used within recommended doses for a stipulated period of time. References A Systematic Review & Meta-analysis of the Effect And Safety of Ginger in the Treatment of Pregnancy-associated Nausea and Vomiting: https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2891-13-20 How Safe is Ginger Rhizome for Decreasing Nausea and Vomiting in Women during Early Pregnancy? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5920415/ Medicinal Value of Ginger with Focus on its Use in Nausea & Vomiting of Pregnancy: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10942910601045297  Imbalanced Sodium & Potassium Levels Increase the Risk of Hypertension Imbalanced Sodium & Potassium Levels Increase the Risk of Hypertension Twins might be identical or non-identical in appearance but their behaviour and characteristics have always been non-identical. Among nutrients too, it is not wrong if we call Sodium and Potassium as twins owing due to the strong relationship between them. These two together play a huge role in regulating blood pressure and are closely involved in bone health. Both of them are electrolytes needed for normal body functioning, fluid balance and blood volume maintenance in our body. The very question now is how much of these nutrients are needed for a balanced life? Molecular pumps pull potassium into cells and push sodium out of them to create a chemical battery that drives the transmission of signals along the nerves thereby empowering muscle contraction. An imbalance in sodium-potassium levels lays the foundation for a number of health problems-too much of sodium content and too little of potassium can raise blood pressure levels but such imbalances have become problematic recently. Long long ago, when man roamed the Earth in search of food he consumed more of fruits, vegetables, leaves, flowers, roots and plant sources (our so-called Palaeolithic diet) which provided humans with abundant potassium and minimal sodium. But now, sodium consumption has gone way above normal limits with the inclusion of processed foods and high-salt meals in our diet whereas potassium levels are far below recommended values due to minimal consumption of produce and other plant-based foods. The body tries to maintain sodium-potassium balance with what we feed to it. Higher sodium levels and lower potassium levels worsens health as the body tries to hang on to the available nutrient, sodium, to compensate for the missing nutrient, potassium. This complicates the situation even more as blood pressure shoots up and the heart muscles are forced to work harder. Its possible to throw out sodium by bringing in more potassium into our system and this proves to be extremely useful in helping the heart and arteries as well. Its sad that the relationship between sodium and potassium and vascular function has not been brought into the limelight as required. Arterial Stiffness Cardiovascular disease is widespread in our world today owing to different reasons. Increased arterial stiffness and wave reflection are independent risk factors that increase the risk of cardiovascular events. Studies show that meals high in sodium content increase augmentation index in normotensive adults and such prolonged intake (more than 2 weeks) in young, healthy males with normal BP increase wave reflection and carotid BP. Thereafter, sodium restriction for the next two weeks improved carotid arterial compliance and augmentation index in elderly people with systolic blood pressure. But potassium’s effect on vascular function has not been explored much, even in those research studies that have dealt with it have inconclusive effects seen and some showed no change in arterial stiffness as well. Multiple trials have given hints that high urinary excretion ratio affects BP levels and cardiovascular disease risk which makes researchers even more interested in knowing the link between sodium and potassium interaction. Effect of Sodium & Potassium Interaction on Arterial Stiffness One study specialized in understanding this link between sodium and potassium and their effect on arterial stiffness. The study included 36 participants who were healthy and young aged around 24 years. Those who were obese, smoking, under medications for cardiovascular/hypertension, with history of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes or renal impairment were disallowed from participating. All the participants were given instructions on the recommended portion sizes and asked to eat as they would normally and include two weekdays and either of the weekend days in the record provided by the research team for noting down eating schedules. Urine samples were collected for calculating free water clearance and fractional excretion of sodium, potassium and chloride. Physical activity levels of each of the participants were tracked and the measurements were noted down. All the participants were informed not to exercise for 24 hours, eat for 4 hours and drink alcohol/caffeine for 12 hours prior to testing. Radial artery waveform was recorded using a applanation tonometry with the help of high-fidelity strain-gauge transducers placed over the radial artery. Central pressures and augmentation index (AI) were obtained from the synthesized wave. AI indicates wave reflection and is influenced by arterial stiffness. Reflection magnitude (RM) was calculated as the ratio of the amplitudes of reflected/forward waves. Carotid-artery pulse wave velocity (PWV) was calculated using tonometry to record carotid artery and femoral artery waveforms simultaneously. Blood samples were taken from all the participants to measure plasma haemoglobin levels. Results All participants had normal BMI ranges, normal iron status and electrolyte levels. Physical activity assessment showed that all the participants expended 1025±279 kcal/day above resting energy expenditure. Average BP measurements were 117±2/63±1 mm Hg. All the subjects consumed around 2200 kcal/day where carbs provided 50% of the energy requirements, 31% were from fats and 18% was from proteins. Women consumed comparatively lower calorie numbers. Sodium intake was around 3763 mg/day which is well above the recommended levels while men consumed more than women. Potassium intake was around 2876 mg/day which is well below the recommended 4700 mg/day but there was no difference between both the genders in terms of potassium consumption. Sodium and potassium intake matched urinary excretion data suggesting that excretion reflects dietary intake. Sodium to potassium ratio was 1.4±0.1 and this is well above recommended numbers of 0.49. Average AI was 2.2% and PWV was 5.2 m/s with females having higher AI rates than males. Though no correlation was found between sodium excretion and AI a significant inverse correlation was found between potassium excretion and AI. There was a significant relationship between sodium/potassium excretion ratio and AI, Tr was linked to potassium excretion and those with decreased potassium intake exhibited shorter time delay of the reflected wave. The link between potassium excretion and PWV showed that those with greater potassium intake have a slower velocity but there were no similar results seen between sodium/potassium excretion ratio and PWV. RM, the ratio of reflected and forward waves was significantly linked with sodium/potassium excretion ratio but not either of the two confirming that both sodium and potassium intake might be important mediators of wave reflection. The study clearly indicates that potassium imposes greater influence on wave reflection in healthy, young adults- lower potassium excretion was linked to greater wave reflection and pulse wave velocity was faster. The China Salt Substitute study compared the effects of a potassium substitute containing 25% potassium chloride to regulate salt levels in individuals with higher risk factor for vascular disease over a 12-month period. Though this substitute incurred time delay in wave reflection there was no changes in AI. Another study by Matthesan et al. probed into the impact of supplementation of 100 mmol potassium chloride daily for 28 days. All the participants had a standard diet consisting of 150 or 200 mmol of sodium depending on energy needs. Results showed a small but significant increase in PWV without changes in AI or BP in the study participants. Other studies looking into potassium effect on wave reflection found that decreased supplementation of potassium did not create much of a difference in results. In our present study, high potassium levels were fed and these were associated with lower AI and a slower PWV. Arterial stiffness plays a significant role in the relationship observed between potassium excretion and wave reflection by encouraging the speed up of reflected wave. There is an inverse relationship between potassium intake, wave reflection and arterial stiffness in young, healthy adults. Increasing potassium levels in the diet helps in reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease besides lowering blood pressure levels. References Lower Potassium Intake is Associated with Increased Wave Reflection in Young Healthy Adults: https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2891-13-39 Potassium and Sodium Out of Balance: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/potassium_and_sodium_out_of_balance  Healthy-weight People are Less Tempted Towards High-calorie Foods Healthy-weight People are Less Tempted Towards High-calorie Foods It’s the time of the year when we are in a festive mood as Christmas and New Year are very near. We are looking into various party options, the best DJ’s who can make our New Year Eve awesome and the best cuisines that could be a treat to our taste buds. Besides these, plans for Christmas meet ups and cake exchange roundups are happening in full swing. Among all this buzz, are you one of the very few who stands grounded resisting all these temptations but enjoys the buffet spread and the food varieties sticking to optimal portion sizes? If yes, it should be highly appreciated as most of us are not wired that way. The sight of a yummy doughnut or a lip-smacking burger dissolves all our resistance to eat healthy food and our mind never becomes satisfied until we eat it. Moreover, New Year is the time of the year where we make commitments to ourselves to become better taking up goals and resolutions that once again disappear into thin air in course of a month or two. Obesity and overweight, two of the most debilitating conditions affecting our health has become a global concern owing to their extreme side effects on the quality of life of individuals. They pave way for serious health problems including cardiovascular diseases, cancers and other conditions as well. Calories consumed is more than calories burned resulting in an energy imbalance that is the root cause for excess fat accumulation in the body. The primary deal now is to identify the underlying mechanisms that trigger such excessive energy intake in order to control the obesity epidemic. We do have a number of research studies probing into the genetic, hormonal and metabolic reasons associated to dietary intake and weight gain. Mankind has strong ties with his previous generations carrying on their genetic traits but the surrounding environment also has equal influence on his/her actions. We safely blame our genes for any negative consequences of our action, for our slow metabolism or even our laziness leaving behind all the efforts that could have helped us overcome these negative effects in life. So, indeed the fact that number of studies helping us understand the underlying and modifiable neural mechanisms that motivate the decisions about ‘what’ and ‘how much’ are fewer in number comes as no surprise to us. Drug and alcohols were some of the common addictions decades back but mankind slowly started digging his own grave by becoming addicted to smartphones, tablets and games. Gaming addiction has been declared as an official addiction by the World Health Organization. Food has been the first love for many who are ready to give up several things for it. These guys can never resist the temptation of highly palatable, calorie-rich foods that’s now been designated as an addictive behavior that’s similar to other addictions. An analysis on those who eat excessive portions reveal that they blindly select their favorite foods thinking about the short-term happiness totally turning a blind eye to the long-term consequences staying put in a situation where they have lost the ability to make optimal food-related choices. Researchers feel that three key neural systems that include the following might provide explanation for the inability to control temptation of food and the development of less-healthful eating habits:

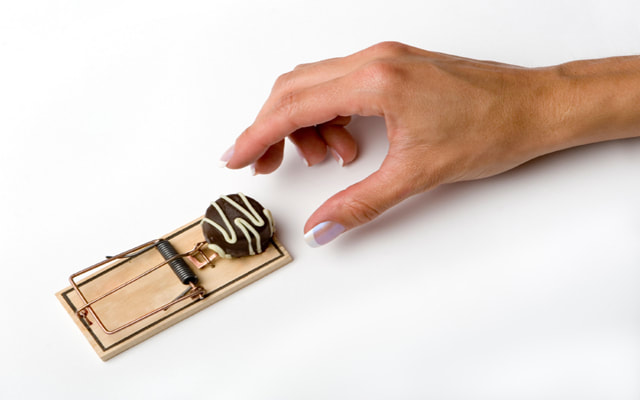

Study on the Neural Systems Triggering the Temptation to Eat Tasty Food The study included 30 young healthy adolescents (17 of them were females) aged around 19.7 years whose average BMI was 23.1. None of them were under treatment for obesity and the research team ensured to exclude those who were suffering from neuropsychiatric disorders, medications or issues such as anxiety, bipolar disorder, psychoses or substance abuse that could affect neuroimaging results with the help of a technique called SCID. All the participants were asked to answer a 41-item questionnaire that probed into the participant’s history of diabetes, hypertension, lungs, heart, kidney or liver disease. Questions on head trauma, neurological diseases, use of any medications, smoking, alcohol use and caffeine consumption were present in the same questionnaire. Participants with positive answers to a history of head injury, treatment for obesity or neurological disease were excluded from the study. All the participants were requested to come for completion of their behavioural task and scan. They were asked to refrain from any intense physical activity 24 hours prior to the scan but there was no restriction in meal and food habits. Height and weight measurements were taken before the scan, 1 24-hour dietary recall was done and the participants rated their hunger level from a scale of 1 (not hungry) to 10 (extremely hungry) to ensure that none of them were in a deprived state. Those who had a score >5 were asked to return back some other time after eating a normal meal. All the participants performed two food-specific go/nogo taks: one low-calorie food go and high-calorie food nogo task (LGo task) and the second, a high-calorie food go and low-calorie food nogo task (HGo task). Cucumbers, celery, broccoli and carrots were some of the foods included in the low-calorie food images while high-calorie food images included cookies, ice creams, potato chips and cookies. Each of them were asked to press a button when they were ready to go to trial and withhold responses to the nogo trials. There were 120 go trials (75%) and 40 nogo trials (25%) occurring in a random order such that Nogo trials also has equal probability as the Go trials also ensuring that no two Nogo trials appeared consecutively. Every image was present for 500ms and every task had a maximum duration of 8 minutes. Results The participants exhibited normal intelligence (IQ) and working memory/functioning. Each of the individuals reported consuming 2.4±1.6 servings/day/1000 kcal of low-calorie foods (fruits and vegetables) and 1.8±1.3 servings/day/1000 kcal of high-calorie foods (such as sugar-sweetened and fatty foods). It was good to realize that all of them consumed more servings of low-calorie foods comparatively irrespective of age and hunger rating. But there was a gender difference reported with females consuming more low-calorie foods than high-calorie foods in comparison to males. Participants made frequent errors and faced hard times inhibiting responses to high-calorie food cues in the LGo task and reaction time was also longer in this task. Participants were willing to press the button more willingly when they were presented with high-calorie food images in the HGo task. Reaction time for the trials in the HGo task was negatively correlated with BMI and high-calorie food consumption indicating that people with higher BMI values responded more readily to high-calorie foods. It was also observed that inhibiting response to high-calorie foods was difficult for individuals with higher BMI and those who consumed more of high-calorie foods. The neural system showed more activation during nogo trials than go trials. The task imposed effect on regions of the brain including bilateral frontal pole, bilateral dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and ACC which were more active during the nogo trials than during go trials. The left occipital pole showed main effect of the stimuli activacted every time when a high-calorie food picture was shown in comparison to viewing a low-calorie picture. There was no interaction seen between task and stimuli in any region of the brain. Activation in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) comparing nogo trials to go trials was negatively correlated with BMI and high-calorie food consumption. Also, females displayed more activation in ACC than males when comparing nogo trials to go trials. Go trial results showed that high-calorie food cues were linked to higher activity in the right striatum relative to low-calorie food cues. Such increased activity in the right striatum was linked to both BMI and level of high-calorie food consumption. Males and females did not show any difference in the activation of the right striatum. The study did show the neural basis that exists as a reason behind one’s loss of ability for self-control when shown tempting food choices and this could be used to bring about intervention strategies to reduce the consumption of high-calorie foods. This in turn reduces the rates of obesity/overweight that’s disrupting the health of people in the society. Pre-exposure of Tempting Food Decreases Temptations Pre-exposure of tempting food in situations that discouraged temptations improved resistance to food temptation thereon. This has been tested in normal-weight people and has shown beneficial results but we don’t have studies until now testing it on obese individuals. It is seen generally that obese people respond differently to tempting food compared to healthy-weight people-they are poor at resisting temptations and value such tempting rewards more. We have a study that took up pre-exposure of tempting food to obese people and its effect on preventing them from succumbing to temptations in due course. The study happened in two different university labs, Greece and Belgium, which included 115 individuals of whom 77 were healthy-wight and 38 were obese participants. All the participants were inquired about their hunger levels (on a 7-point scale) and were informed of their participation in a word fluency test. Each of them was randomly assigned to a candy scrabble game (pre-exposure condition, PE) or a foam scrabble game (control condition, CTR). Each group received 30 letters which was used to form words during the game. Then, each of them received two bowls of the same volume of a tempting snack and the samples were named as A and B though in reality both the bowls contained the same snack. Each of them either received two bowls of peanut M&M’s or two bowls of Maltesers. Each of the participants were asked questions such as ‘How crunchy are these chocolate candies/crunchy nuts?’ ,’to what extent do they melt in the mouth’, etc. Results Difference in the sample with respect to age and gender was observed with no difference in the average BMI. No difference in hunger levels was observed between the healthy and obese participants and within the obese group no difference in hunger levels was observed for CRT and PE condition. In the PE condition hunger levels were higher than in the CRT condition for obese participants while the healthy-wight participants ate less. In health-weight participants, those who performed the scrabble test with candy letters (PE) ate significantly less during the subsequent taste test than the group that performed the task with foam letters. Obese-weight participants in both the groups consumed a similar number of tempting snacks. In the control group, the obese-weight participants ate less than the healthy-weight participants but the same did not happen in the experimental group. The study showed that pre-exposure helped healthy-weight participants to consume less but the same was not observed in obese individuals. References Poor Ability to Resist Tempting Calorie Rich Food is Linked to Altered Balance between Neural Systems Involved in Urge & Self Control: https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2891-13-92 Pre-exposure to Tempting Food Reduces Subsequent Snack Consumption in Healthy-weight but not in Obese-weight Individuals: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00685/full Weighing above normal weight ranges and wishing to try running or Zumba? Not many recommend doing these as they fear applying increased stress on the knee might disturb it contributing towards joint pain and more. Overweight/obese people are generally recommended to pursue walking as the primary exercise form to reduce a certain amount of weight before moving on to other more intense ones such as jogging, running, playing a sport and likewise. But there are many controversies surrounding the fact whether running is harmful to the knee, especially if it would induce osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the common form of arthritis that exists as a leading cause of disability, especially in the elderly population and those participating in sports activity. Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is one of the primary causes of long-term disability in the world that can result in chronic pain, limit activity level and decrease quality of life of the affected individual. Age, obesity and genetic factors are the primary risk factors for KOA which can be greatly eliminated by performing regular physical activity. But sadly, not even a quarter of the world population meet the recommended guidelines of performing 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week. Not many individuals take up exercise as a serious means to fight knee osteoarthritis and it becomes the physician’s burden to deliver the required exercise performance from the patient. Walking is the best preferred option by physicians but running exists as one of the popular activity forms among individuals as it bestows numerous psychological and physical benefits on the individual. But running has always remained as an activity form that has been negatively associated with knee joint health (since the knee exists as one of the frequently used body parts in runners). Chronic mechanical overloading can damage structures within the knee. But there are also opinions that runners generally have a lower body mass index compared to non-runners that could protect them against knee osteoarthritis. We have data supporting and opposing the effect of running as an exercise: AlentornGeli et al. related recreational running with lower rates of KOA while competitive running was linked to higher rates. Though research on this topic is growing day by day the absence of precise knowledge on the understanding between KOA and running is absent until now. We also have data showing that long-distance running might be linked to progression of knee OA in the absence of knee injury, obesity or poor muscle tone. OA results in higher disability rates leading to increased rates of hip and knee replacements. Running, an exercise form, that exists as the favourite among millions of individuals is now at the junction of also existing as one of the causes of knee osteoarthritis. Even an elevation in BMI causes a raise in the risk of OA. Studies that Support or Reject Running as a Risk Factor for OA A longitudinal study on long-distance runners and controls suggest that disability levels in runners increase with age at 25% of the rate of more sedentary controls. When the study was designed in 1984 there were serious concerns that running could accelerate OA due to repetitive trauma to the joints. The study is a long-term one conducted for a period of 18 years with a hypothesis that long-distance runners were prone to more severe OA than aged populations. The study included long-distance runners aged ≥50 years who had been into running for more than a decade. The control group was selected from a random sample thereby assembling a cohort of 538 runners and 423 controls who met the eligibility criteria. Weight-bearing radiographs of the knee was taken in 1984, 86, 89, 93, 96 and 2002. During the 18 years of study, radiographs of the knee was taken for both runners and the control group. After a series of eliminations and due to unfavourable reasons only 113 participants remained in the radiographic study and of them, 98 (45 runners and 53 controls) had at least two sets of radiographs. All participants provided information on demographics, medical history, BMI, exercise routines, injuries and functional status. The total time spent on performing vigorous-intensity exercises such as running, swimming, brisk walking and aerobic dance was noted down. Participants in the intervention group were slightly younger, had a lower BMI and reported a greater prevalence of knee injury than the controls. They had also decreased their running time by 55% at the end of the follow-up period but maintained overall time spent in vigorous-intensity exercise (almost 300 minutes/week). In the control group, a small proportion of them were involved in running as an exercise form and all the controls increased their overall time spent in vigorous activities by 100 minutes/week and this was mostly brisk walking. There was a significant difference in the time spent in running between the intervention and control group throughout the study. Results Most of the participants showed little OA at the start and end of final radiographs. Though total knee scores were worse in runners at baseline compared to controls the scores of both the groups at the end of the study remained the same. Joint space width (JSW) of the worst knee was worse among runners than controls at the initial radiograph but was nearly identical at the final assessment. While two participants in the control group had undergone knee replacement there were none in the runner group with such need for replacements. Three controls had a JSW of 0, one participant in the runners group had a JSW of 0 and only 10 participants (6 controls and 4 runners) had JSW in the worst knee ≤1 mm. Total knee score (TKS) remained low for all participants at the final radiographs. The mean TKS was 3.6 for runners and 4.2 for controls while the possible scores can be between 0 and 36. The study result is consistent with some other long-distance running study results that show that running may not be an independent risk factor for knee OA. But we also have a number of studies that show that participation in specific sports at the elite level does increase the risk of knee OA. This study is an example for the fact that long-distance running should not be discouraged among healthy older adults fearing progression of knee OA. Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) In the OAI there were more than 2000 participants who completed a survey of exposure to leisure-time physical activities and the study dealing with the effect of running on KOA is a cross-sectional study nested within the OAI in men and women aged between 45 and 79 years who showed no symptoms of OA nor had high risks for the same; or were at a high risk for developing OA or already had knee OA. All the participants were asked to complete a questionnaire which probed into 37 leisure-time physical activities that included jogging or running. All the participants were asked to identify activities that they performed for at least 20 minutes in a day at least 10 times in their lives during the age periods of: 12-18, 19-34, 35-49 and ≥50 years old. 3 most frequently performed activities by each of the participants were identified during those age periods and information regarding them were recorded. Those individuals who mentioned running or jogging among the top 3 activity list were defined as runners in that specific age period. At the 48-month visit the participants were asked to report on any knee-specific pain or stiffness. BMI, height, weight and reports on any knee injuries were reported at baseline and during annual visits. After database search, elimination and selection the study included 2,637 participants of which 55.8% were females, 634 of them were from the progression cohort (had symptomatic OA at baseline), 1,899 were from the incidence cohort (did not have symptomatic OA but had high risk of developing the same during follow-up) and 104 were from the nonexposed control group. 778 of the participants had been engaged with running at some point in life but only 2-5% ran competitively. Results showed that any history of running was associated with less frequent knee pain, had lower odds of radiographic and symptomatic OA compared to those who never ran in the unadjusted model but when adjusted for BMI, height, weight, sex and leisure-time physical activity that significantly correlated with running during the relevant time frame there was no significant difference found. There was no link found between running and either injury or BMI in any of the 3 outcomes. Studies show that injuries can occur in 7-50% of runners and because of this, runners are expected to be at a high risk for knee OA but there was no such risk found in the present study. The researchers attribute this to the lower BMI seen in runners compared to non-runners. This study shows that running does not cause harm to the knee in any way and those with lowest BMIs were involved in running as a major activity form in their lives. Perception of Individuals & Physicians about Running and Knee Health in Canada A cross-sectional survey was conducted in the Canadian population and once individuals agreed to participate, the respondents placed themselves in one of the five subgroups based on their profiles: non-runners without KOA (NRUN), non-runners who have received a diagnosis of KOA (NRUN-OA), runners without KOA (RUN), runners who have received a diagnosis of KOA (RUN-OA) and healthcare professionals (HCP) from different backgrounds. All the participants were asked to fill questionnaires that contained a series of questions pertaining to the study. A total of 114 non-runners, 388 runners and 329 HCP completed the survey. Results showed that 13.1% of public respondents perceived running as an activity that hurt the knee and 25.9% of them were uncertain of the effect. A great number of participants belonging to the NRUN and NRUN-OA group had a negative perception compared to the RUN group, 8.2% of the HCP felt that regular running was bad for knee joint health but 78.1% of them disagreed on this point. There was a negative perception felt by 3.9% of HCP who ran and 15.2% of HCP who did not run. Only 7.6% of the public felt running to be an activity that leads to KOA but 33.9% of them were unsure about it. Only 2.7% of the RUN population felt running to be detrimental to knee health compared to 23.1% of NRUN and 24.2% of NRUN-OA population. 15.5% of the public felt that running marathons or long-distances would end up in KOA while 43.6% of them were uncertain of the results. But 47.9% of the RUN, 15.4% in NRUN and 19.4% in NRUN-OA disagreed with this result. On the whole, 17.9% of the public felt that running with KOA would lead to profound knee damage, 48.4% were uncertain and 32.7% of the NRUN population and 46.8% of the NRUN-OA population agreed with this statement than the run subgroup. 41.9% public felt that running with KOA was ok on days when there were no symptoms felt but 39.5% were uncertain about it. But it was 12.4% of the general public who felt that running with KOA was a means to accelerate the need for a total knee arthroplasty but more than 50% of the public were confused regarding their stand in this. 30.8% of NRUN and 37.1% of the NRUN-OA population agreed compared to 5.4% of the run population. The study shows the clear confusion existing among individuals with regards to running and its effect on KOA. All these studies show that evidences are still inconclusive and the risk of developing OA has to be identified individually presently. There is no way in which we can conclude on the role of running in knee OA with these results. References Long-distance Running & Knee Osteoarthritis A Prospective Study: /https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2556152/ Is There an Association between a History of Running and Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis? https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/acr.22939 What are the Perceptions about Running and Knee Joint Health among the Public & Healthcare Practitioners in Canada? https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0204872 Liver, an important organ in the human body, is not much talked about despite its versatility in fighting against infections, aiding in digestion, storing energy and cleaning the blood. This organ residing in each of us contains a designated amount of fat which is normal but the problem arises when more than 5-10% of the liver’s weight is fat resulting in what is termed as a fatty liver. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the build-up of excess fat in the liver cells that’s not a result of alcohol commonly seen in overweight or obese people. NAFLD can be split into four stages that includes simple fatty liver (steatosis), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis and cirrhosis (here, the individual is at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)). Many people get into the first stage even before realising what’s happening but it can take years together to reach the 3rd or 4th stage before which significant lifestyle changes can prevent this condition from worsening. Otherwise, such high fat accumulation in the liver paves way for other serious health conditions such as diabetes (this once again increases the risk of heart disease), high BP and kidney disease.

Prevalent rates of the disease are different in different parts of the world with maximum prevalence of 20-30% recorded in Western countries. Earlier days saw the need for humans to hunt or gather food for fulfilling nutrient requirements and this included energy expenditure to replenish the lost energy with food. But now, despite the prevalence of malnutrition and poverty among a class of people there are a majority of individuals who are provided with a surplus of daily calories thereby increasing the rates of obesity and overweight worldwide. This kind of an obesity epidemic has made it possible for diseases such as NAFLD to become diagnosis of chronic liver disease. Though it can affect any individual of any age it is generally the middle-age people who are affected. Though there are different treatment plans proposed for NAFLD weight loss and lifestyle management exist as the most reliable forms of treatment plans till date. We have research supporting the fact that lifestyle interventions reduce markers of liver lipid and metabolic control along with reducing intrahepatic lipid (IHL) and studies even show that increased exercise practices are linked to lower levels of IHL but it is also essential to remember that weight loss is difficult to achieve and even more difficult to maintain. Even The American Gastroenterological Association, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology all of them recommend physical activity as one of the best treatment methods for NAFLD. Given below is a detailed study of hbow exercise affects NAFLD. Aerobic Exercise As a Tool Against NAFLD A non-randomized clinical trial segregated 90 NAFLD patients into two groups-case and control groups. Height, weight and BMI calculations were made on each participant. Liver enzymes (AST, ALT, ALP), fasting blood sugar (FBS) and lipid profile (TG, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol) were measured. In the case group, when TG levels were above 400 mg/dl enzymatic method was used for calculating LDL cholesterol and in the control group, medical therapy with 1000 mg vitamin C and 400 units vitamin E were prescribed. Besides medical therapy (just like the control group) 30 minutes of aerobic exercise with maximal heart rate thrice a week for around 3 months was performed in the case group. Of the 90 participants 57 of them were men and 33 were women. In the case group, 29 were men and 16 were women while in the control group 28 were men and 17 were women and all of them were between 17 and 56 years of age. Once both groups were done with their stipulated duration of aerobic exercise performance serum levels of enzymes and liver echogenicity in individuals with NAFLD was decreased. It was observed that in the case group, 35 patients were in stage 1, 4 and 6 patients were in stage 2 without sonographic fatty liver. In the control group, 33 patients were in stage 1, 9 patients were in stage 2 and the fatty liver of 3 patients was resolved by sonography. Weight, BMI FBS, TG, HDL, AST, ALT and VFM values varied significantly before and after the trial in the case group. In the control group there was significant difference found in weight, BMI, SBP, DBP, TG and LBM values before and after trial. Effect of Resistance Training on NAFLD 21 NAFLD patients leading a sedentary lifestyle were involved in the study and each of them were randomly assigned to either the exercise (11 participants) or standard care (10 participants) group respectively. Physical examination, full medical history and fat measures (both subcutaneous and visceral) were done on each of the individuals. The exercise group performed resistance exercises on non-consecutive days for a period of 8 weeks for around 45-60 minutes daily with 10 minutes of warm-up session before the exercise. The programme involved eight exercises and the participants were encouraged to increase resistance used every week when possible. While 2 participants were removed in between the research quoting various reasons the other 19 participants completed the study. Results showed that BMI remained unchanged in both the groups during the study with insignificant changes seen in weight, waist or hip circumference, waist to hip ratio, body composition and visceral or subcutaneous fat in either group. There was a 13% reduction in IHL values witnessed in the exercise group on performance of resistance training with no changes seen in the control group. Three participants in the exercise group witnessed great improvements moving over from having significant NAFLD to staying within normal limits whereas none of the control subjects moved into the normal liver fat range. The exercise group also showed improved glucose control and significant improvement in insulin sensitivity. Fasting glucose levels also reduced in the exercise group after intervention compared to the control group. The study is a clear example that resistance exercises reduced IHL, increased insulin sensitivity and improved metabolic flexibility in NAFLD patients independent of weight loss. Evidences in Favour Of & Against Exercises End-stage liver disease (ESLD) and HCC are the final outcomes of fatty liver disease and we don’t have studies until now showing the effects of exercise on them. But logically, when individuals recover from NASH the risk of going into any of the other stages is minimal. A randomized control study by Eckard et al. focusing on lifestyle interventions that included daily physical activity showed significant reduction of NASH score. Another RCT on 31 NASH patients showed that 48 weeks of intense intervention pave way for a 2.4-point reduction of score. A 2012 meta-analysis done by Keating et al. on 439 subjects showed only a small reduction in liver fat content. A systematic review by Golabi et al. on 8 randomized trials on 433 individuals showed a 30.2% reduction in hepatic fat that was a result of regular exercising and a 49.8% reduction in liver fat that’s a result of a combination of both exercise and dietary intervention. There are a couple of studies that focused on the modality, intensity and duration of exercise that had a definite impact on NASH patients. An analysis of 813 NAFLD patients who were asked to self-report on their physical activity status came to the conclusion only those patients who performed vigorous physical activity were at a decreased risk of entering the NASH stage and those patients who doubled the exercise intensity decreased their risk of advanced fibrosis even further. Another study in Japan focusing on five cycles of HIIT training followed by 3-min recovery periods showed an optimal reduction in liver fat. Another study segregated 48 patients randomly into four different groups-low-intensity/high-volume, high-intensity/low-volume, low-intensity/low-volume and no exercise. While each group did experience a significant reduction in liver fat there was not much difference witnessed between the regimens. This shows that aerobic exercise done even at low-intensity reduces fat content of the liver. Another study by Bacchi et al. compared the effects of aerobic versus resistance training on 31 NASH patients over a 4-month period. While liver fat content did reduce there was no difference in results seen between the two exercise forms. A randomized trial on 196 subjects showed that aerobic exercise resulted in a greater reduction in hepatic fat content than resistance training program. But all these studies had one ideology in common-hepatic fat content decreased even when there as no change in weight loss observed in different studies. This clearly shows that physical activity and exercise have a direct impact on the liver. References The Effect of Physical Exercise on Fatty Liver Disease: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5954622/ The Effect of an Aerobic Exercise on Serum Level of Liver Enzymes & Liver Echogenicity in Patients with Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4017540/ Resistance Exercises Reduces Liver Fat & its Mediators in non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Independent of Weight Loss: https://gut.bmj.com/content/60/9/1278 Our moms and grandmas are leading longer lives than expected seeing their grandkids and great grandkids attend school and college! They belong to a generation who is blessed to witness such a sight in their life and all this is because of advancements in science, especially in the field of health care. Life expectancy of the elderly generation is reaching new highs and so are their obesity rates. That’s because, ageing is accompanied by changes in body composition of individuals. Above the age of 70, both fat free mass and fat mass decrease with fat mass being redistributed in the visceral component and fat deposits are significantly visible in the skeletal muscle and liver. Body fat is mainly determined by the difference between energy intake and energy expenditure. Though there is no great increase in intake portion sizes in the elderly population their physical activity levels also witness a downslide and such decreased energy expenditure plays a prominent role in increasing fat mass with ageing. Also, there is a 2-3% decrease in resting metabolic rate every decade after the age of 20 and all these together account for decrease in energy expenditure with ageing.

But the actual question is whether obese elderly individuals must try to lose weight! For some of you who wonder what’s the point in asking questions when one is obese and there are clear evidences that obesity is a serious risk factor for heart diseases, diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, I guess you have not heard of the obesity paradox! According to it, certain studies and meta-analyses show that a higher BMI can be protective of the elderly population decreasing (instead of increasing) their risk of death. There are various population-based studies that show that weight loss is linked to an increase in mortality rates; weight loss increases muscle loss (sarcopenia), there is a loss of the protective effect of fat (such as against hip fractures) and fat loss also exists which releases fat-soluble toxins into circulation. The next question is whether BMI is a good measure of body fat? In fact, it is not! People sometimes tend to lose height due to bending of the spinal cord as they age and, in such cases, some of them seem to have a higher BMI when their weight has not changed at all. Also, muscle loss, fat distribution and fat increase are not evident in BMI values. In such cases, waist circumference (WC) acts as a perfect measure for calculating obesity in older adults as this gives a clear picture of total fat and intra-abdominal fat. WC is extremely cost-effective, useful and can give a clear picture of the visceral fat adiposity levels in an individual. WC is one of the five criteria that defines metabolic syndrome which is in the first place linked to functional decline, frailty and disability. While ageing itself brings about disability, functional decline and loss of mobility studies show an association between BMI and mobility impairment. But there are very few which focus on WC as a factor for functional decline, falls and decrease in quality of life. Osteoarthritis (OA) is yet another reason for diminishing functional abilities in the elderly population and it also has the ability to increase changes in body composition that occur with aging. A study specifically focused on a cohort of older adults at risk for OA probing whether increased WC impacted quality of life, physical activity and daily life activities in these people. Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) Osteoarthritis initiative (OAI) is an observational study of osteoarthritis in adults aged between 45 and 79 years belonging to any ethnic group. Those suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, severe joint space narrowing, bilateral total knee replacements, unable to undergo an MRI, unable to provide blood samples or having any comorbidities were excluded from participating in the study. Baseline information in the form of questionnaires, interviews and physical assessment were collected. Every participant went through follow-up assessments annually and the present study used six-year outcome data for analysis. All the study participants were put into one of the three subgroups-clinically significant knee osteoarthritis at risk of disease progression, subjects at high risk of developing clinically significant knee OA (incident) and control group. Individuals in the progression subgroup complained frequently of knee symptoms or radiographic tibiofemoral knee OA in at least one native knee. Though the incident subgroup did not have baseline symptomatic knee OA they had certain other risk factors such as the presence of heberden’s nodes in both hands, increased weight, previous knee injury or operation, family history and pain in the knee on most days of the preceding month. The control group neither had pain nor risk factors or radiographic findings. Results The study consisted of 2,182 subjects whose height, weight and waist circumference were measured. Waist circumference was measured at the level of the umbilicus between the lower rib and the iliac crest. BMI was calculated as weight divided by height squared. Gait was calculated using the 20m walk test using which each of the participant’s walking speed was noted down. The study also measured occupational, household and leisure activities using the physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE) which is a 26-item questionnaire with greater scores indicating higher intensity of activity. Results showed that there was a higher proportion of women in the lower WC quartile and the number of medications increased with increasing WC quartile. Also, the proportion of individuals with knee OA increased by quartile. The study compared individuals who participated in the research to those who were excluded and found that the excluded individuals were older, less likely to belong to the female sex and were likelier to have higher comorbidities score and medications. They also had lower SF-12 (quality of life score) score at baseline but there were no differences found in PASE scores. The outcomes were measured at baseline and six years after start of study-it was found that SF-12 rates dropped as waist circumference increased at baseline and follow-up. A decline in PASE score was also observed over time and also between groups at baseline and 6 years after follow-up. Late-life disability index (LLDI) scores decreased at follow-up and activities of daily living (ADL) impairments increased significantly from 18% in the lowest WC quartile to 36.6% in the upper WC quartile. SF-12 values were observed to be age-dependent and those in the high WC quartile had lower scores than the lowest quartile. High WC quartile subjects had decline in PASE score compared to other categories but this was evident only in the 70+ age group. LLDI score also had maximum impact in the same age group compared to the low WC quartile. Also, gait speed was lowest in the highest WC quartile compared to other categories. Patients with OA had lower outcome measures compared to the low WC quartile. The study is a clear indication that high waist circumference is linked to decreased quality of life and physical activity. Hence, rather than focusing on BMI the primary focus must be to improve functional stability, manage weight and increase physical fitness in such a way that there is an overall improvement in physical performance and quality of life of the elderly individual. References The Impact of Waist Circumference on Functional and Physical Activity in Older Adults: Longitudinal Observational Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative: https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2891-13-81 Obesity in the Elderly: More Complicated than You Think: https://www.mdedge.com/ccjm/article/96020/geriatrics/obesity-elderly-more-complicated-you-think/page/0/1 Obesity in the Elderly: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532533/ It’s not surprising when many individuals enroll for a gym membership or a weight loss program with the only aim of losing tummy weight. You might be slim and trim but there might be a small tummy protruding out of your Western outfit that screams for immediate attention. Some people accumulate fat around their thighs, some around their hands and hips but a majority of the individuals suffer from fat accumulation around their tummies (men are primary victims here). Worldwide, obesity and overweight have catapulted the lives of many and according to WHO, obesity is the accumulation of excess body fat that might impair health. Obesity rates have doubled since the 1980s becoming one of the primary reasons for the widespread prevalence of metabolic disturbance owing to increased intake of processed foods that are overloaded with sugar and unhealthy fats. Such excess fat accumulation have debilitating effects on the body’s health increasing levels of bad (LDL) cholesterol, lowering good (HDL) cholesterol levels, hinders body’s response to insulin thereby increasing blood sugar levels and prevails as the major risk factor for numerous diseases including heart attacks, strokes, high blood pressure, cancer, diabetes and even depression.

Abdominal Fat Any type of fat is bad and overweight is not appreciated but when it comes to health there is more concern placed on how much abdominal fat you have and not on how much you weigh. Though BMI exists as the commonly used measure for determining a person’s health this is not an exact measure as BMI only calculates total body fat without regarding how the fat is distributed. So, why does abdominal fat hold more importance than total body fat in determining a person’s health? Though we don’t have exact reasons scientists are indeed coming up with numerous convincing reasons for the same. Abdominal obesity (AO) is excess fat stored in two different abdominal regions-subcutaneous and visceral. Subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT)is located in fatty tissues just beneath the skin acting like fat that’s present everywhere else in the body. This is neither too harmful nor helpful. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is that fat which is located around the internal body organs that exists as the primary health hazard. Such visceral obesity was linked with the overactivity of the body’s stress response mechanisms that raise blood pressure, blood sugar levels and heart risk. So, if BMI is not right maybe an MRI or CT would help us in measuring the amount of visceral fat. But not everyone can afford this right? One of the simpler methods is to measure the waist-to-hip ratio-a ratio measure above 0.95 in men raises the risk of heart attack or stroke while in women it is 0.85. But, much more convenient is the waist circumference (WC) that includes only one and not two measures. In today’s junk food world, there are a number of factors that contribute towards pronounced WC and VAT stores including sedentary lifestyle behaviours, absence from exercise routines and consumption of fatty and sugar-enriched foods. Research shows that VAT increases by more than 200% in men and almost 400% in women between the ages of 25 and 65. Besides food habits, smoking, alcohol consumption, age and hormones increase the risk of abdominal obesity. It has also been observed that VAT levels increase during pregnancy and menopause starting right from perimenopause and going up to the end of menopause. Getting Rid of Abdominal Fat: A Click Away? It is common these days to see ads and social media marketing platforms trying to lure clients by coming up with newer ideas and weight loss gimmicks including the ones such as: the secret pill for belly fat reduction or “Dissolve belly fat within 10 days by drinking this daily!” This makes it even more difficult for health and nutrition experts qualified in diet and nutrition counselling to come up with better solutions that are practical yet effective to help people stop from falling a prey to such gimmicks and take up the best solution to correct abdominal obesity. The right approach is to follow a healthy diet by creating recommended calorie deficits suitable for the individual’s body type and practicing daily exercises. The point now is whether there are specific dietary approaches, nutrients suggested or foods recommended to fight abdominal obesity. Given below are some of the studies that have dealt dealing with abdominal obesity with dietary and exercise measures. Meta-analysis & Review of Randomized Control Trials Though we have studies showing the effect of exercise on abdominal fat there are not many reviews that deal with lifestyle interventions for AO. Databases such as Medline and Embase were searched thoroughly for randomized control trials (RCTs). A 12-month data was used for the study independent of the length of the intervention. Though the search came back with more than 2900 records, there were 15 trials selected for analysis based on different restriction criteria. All except 3 were lifestyle interventions that proposed diet and physical activity changes. Each of the study included anywhere between 34 and 439 participants and the studies were conducted between three months and three years. Results showed that participants in a behavioural change program reduced WC by -1.88 cm and those in a combined program lost a mean of -4.11 cm. Meta-regression analysis showed a mean difference of -2.39 cm between both types of programs showing that a combined approach is the best way possible. Three studies focusing on gender observed that male participants lost a mean of -2.61 cm WC and female participants reduced their WC by -1.63 cm. Of the six studies that practised combined intervention, four chose a physical activity (PA) component, one a very low-calorie diet and another one tested diet and PA separately as well as combined with the combination giving the best result. Effect of Diet on Postmenopausal Women The study here focused whether exercise in combination with diet restriction reduced abdominal fat to a greater extent that one triggered by diet alone. This study is a secondary analysis of the SHAPE-2 study (SHAPE was the Sex Hormone and Physical Exercise study designed to find out the effect of weight loss with/without exercise on biomarkers of postmenopausal breast cancer risk) in which 243 healthy overweight or obese postmenopausal women participated. Eligibility criteria included postmenopausal women, having a BMI between 25 and 35, insufficiently physically active and not diagnosed with diabetes or cancer. There was a 4-6 week run-in period at the start of the study in which a personalized standardized diet that conformed to the Dutch National Guidelines for a Healthy diet (50-60% carbohydrates, 15-20% protein, 20-35% fat, a max of 1 alcoholic drink daily, >25g of fibres per day, 200g of vegetables and 2 servings of fruits) was prescribed. The run-in period was mainly designed to find out the macronutrient intake among participants and stabilize body weight. Study participants were split into one of the three groups: diet group (97 participants), exercise plus diet group (98 participants) and control group (48 participants) respectively. The intervention programs were designed with an aim of reducing 5-6 kg of body weight in 10-14 weeks’ time. Dietitians and physiotherapists monitored the participants’ weight loss performance and self-weighing was performed. When weight loss did not meet or exceed 0.5 kg/week in participants for 3 consecutive weeks there was extra attention given to these participants to change their diet or exercise routine. After weight loss goal was achieved, a weight maintenance (2-6 weeks) was started that included balancing between intake and expenditure levels. Participants in the diet group were given a diet with a calorie restriction of 3500 kcal/week and asked to maintain their regular physical activity. Participants in the exercise plus diet group followed a 4h/week exercise program (this included an energy expenditure of 2530 kcal/week). The exercise program included two 60-min group sessions of combined strength and endurance training conducted by physiotherapists and two 60-min Nordic walking session per week. This exercise intervention was combined with a small caloric intake restriction of 1750 kcal/week to enable 5-6 kg weight loss in a short time. All participants were regularly monitored by phone calls from dietitians. Results Abdominal fat measurements (subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue (SAAT) and intra-abdominal adipose tissue [IAAT]) were taken at baseline and after 16 weeks. SAAT and IAAT were summed together to obtain total abdominal adipose tissue (TAAT) measurements. Total body fat, lean mass, height and body weight measurements were also taken. At the end, 92 women in the diet group, 94 in the exercise plus diet group and 45 in the control group completed the study. Almost 70% of women at least attended four diet-group sessions and 81% attended the group exercise session. Participants in the diet group lost -4.9 kg and -5.5 kg in the exercise plus diet group. There was a -2.8% and -4.4% decrease in body fat percentage with diet and exercise plus diet group respectively. Exercise plus diet group lost more body fat percentage compared to other groups. Compared to the control group, TAAT, SAAT and IAAT decreased significantly in both intervention groups. TAAT and SAAT decrease was significantly larger in the exercise plus diet group compared to the diet group-a difference of -15 cm2 for TAAT and -11 cm2 for SAAT. There was slightly more decrease seen in IAAT measurements in the exercise plus diet group than in the diet group compared to control. The study found a 6-7% weight loss in healthy and overweight-to-obese postmenopausal women that led to a reduction in both intra-abdominal and abdominal subcutaneous fat. Weight loss that occurs as a combination of both exercise and calorie restriction paved way for enhanced changes in subcutaneous abdominal fat but with no changes in intra-abdominal fat when compared to weight loss induced by calorie restriction only. Recent Trends in Managing Abdominal Obesity Intermittent Fasting (IF): Though there is no standard protocol followed for intermittent fasting the general approach includes some level of fasting or energy restriction for 1-3 days/week with or without restriction on the remaining days. But a systemic review of 12 studies comparing IF with continuous energy restriction diets showed that all diet patterns resulted in similar weight loss and reduction in waist circumference irrespective of fasting or energy intake timings followed. High Protein Diet: Proteins have always been considered as a friend of weight loss as it gives enhanced satiety and resting energy expenditure. But there are no convincing evidences from studies showing that a higher protein diet reduces abdominal obesity compared to other energy-restricted diets. Palaeolithic-style Diet: This diet trend tries to mimic the eating habits of our early Palaeolithic age ancestors that includes elimination of certain food groups and foods not available during the Palaeolithic era. There are very few studies that focus on this diet as a means to reduce abdominal obesity and the information from them are also not convincing to say that a Paleo-style diet is a good target to curb abdominal obesity. Green Tea: Green tea has been sought after for its benefits in effective weight loss including reducing abdominal obesity. Green tea catechins (GTC) have been said to have a synergising effect on energy expenditure, fat absorption and fat oxidation. Although GTC show advantages in animal studies the dose needed for creating significant difference in WC in humans display unrealistically high quantities. DASH & Mediterranean Diets: The NIH-developed Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and the Mediterranean diet were selected as the “2018 Best Overall Diets” as both of them are great options to encourage individuals to incorporate them in their daily lives for weight loss benefits. The DASH diet promotes weight loss and reduces risk of heart disease while the Mediterranean diet leads to lower cardiometabolic disease rates. There is no one specific magic diet, food or ingredient that can promote weight loss, especially abdominal obesity reduction. It is always better to eat a healthy diet and perform regular physical activity to lose weight and stay healthy. Don’t get swayed away by misleading information about the latest trends for belly fat. It is always better to get in touch with registered dietitian nutritionists to get yourself going with the best diet plan that suits you instead of going behind those that eliminate food groups or promote fasting as a means to lose weight. References Therapeutic Treatment for Abdominal Obesity in Adults: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6121087/ Effect of Diet With or Without Exercise on Abdominal Fat in Postmenopausal Women- A Randomized Trial: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-019-6510-1 Targeting Abdominal Obesity Through the Diet: https://journals.lww.com/acsm-healthfitness/Fulltext/2018/09000/TARGETING_ABDOMINAL_OBESITY_THROUGH_THE_DIET__What.8.aspx?WT.mc_id=HPxADx20100319xMP We live in a period in which overweight/obesity rates are overpowering normal body weight in kids and adults equally. While dietary factors hold primary responsibility its also our sedentary lifestyle and physical inactivity that play an equal role in triggering excess body weight in kids, adolescents and even toddlers. This excess body weight now exists as one of the biggest medical problems around the world affecting people from all walks of life disrupting their quality of living. Some of the major long-term issues include diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, sleep apnea, musculoskeletal problems, gastrointestinal disease and psychosocial difficulties. Overweight/obese kids (above the age of 7) have maximum risk of growing into obese adults with increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Even the World Health Organization (WHO) shows that overweight and obesity exist as the leading cause of premature death worldwide and as a serious risk factor for mortality during adulthood too.

Obesity is nothing but body weight ranges well above the defined limits which leads to higher body mass index values and waist circumference. Statistics show that obesity rates in America have more than doubled in the past few decades and the results are almost similar elsewhere too - India is becoming one of the top countries with maximum childhood and adult obesity rates, the incidence of obesity and overweight in the Iranian population is 10.1% and 4.79% respectively and Brazil has experienced a drastic nutritional transition from decrease in malnutrition to increase in obesity/overweight rates. Though genetics and environmental factors do play an integral role in determining obesity risk in kids most researches also show that macronutrient composition of the diet is equally important to maintain normal body weight. Studies focus on dietary fats and carbohydrates too as a factor for weight control. Carbohydrate Quality Using Glycemic Index Some of us have heard the term glycemic index while for others it might be something new. It was Jenkins et al. (1981) who used the term ‘glycemic index’ first to define carbohydrate quality. What is this glycemic index (GI)? It is nothing but the ability of the food to increase blood glucose 2 hours after eating that kind of food. According to Jenkins GI refers to the area under the blood glucose curve measured two hours after consuming 50g of carbohydrates with respect to the results obtained by consuming 50g of glucose or white bread. The term glycemic load (GL) was introduced in 1997 to quantify the overall glycemic effect of food with respect its specific carbohydrate content in typically consumed quantities. GL is calculated by multiplying amount of GI with carbohydrate amount in grams. High GI and GI diets are rapidly digested, absorbed and transformed into glucose which pave way for higher chances of glucose fluctuations, early signs of hunger and increased calorie consumption. Meanwhile, a low GI and GL diet takes time for digestion, releases glucose and insulin slower into the bloodstream and increases satiety levels decreasing calorie consumption. Maybe some of you now remember our physician’s clinic or hospital that notifies patients on the list of low GI and high GI foods that need to be consumed and avoided. But studies on the relationship between these indices with obesity rates in individuals come up with controversial results-either supporting, rejecting or showing no changes between the indexes and obesity rates. A meta-analysis published in 2003 shows that low glucose index (LGI) are advantageous for glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in type 1 and type 2 diabetics compared to high glucose index (HGI) diets. We do have studies showing that consumption of high GI/GL diets increased the risk of type 2 diabetes. But most of these studies focus primarily on the adult population and the study below shows the effect of LGI and LGL on anthropometric parameters, blood lipid profiles and indicators of glucose metabolism in kids and teens below 18 years of age. Systemic Review The systemic review was performed using the electronic databases MEDLINE and EMBASE with search terms such as ‘glycemic index’ and ‘glycemic load’. Apart from keywords other inclusion criteria were that they must be randomized control trials (RCT), age of participant <18 years of age, they must be humans and markers such as BMI, height, weight, waist circumference, hip circumference, waist-to-hip ration, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and fasting serum insulin (FI) must exist in the studies. The search came up with a total of nine studies consisting of 1359 articles and 1065 participants that met the study criteria and was now eligible for meta-analysis. All the nine studies were randomized control trials (RCTs) which had a duration between 10 and 96 weeks. Results showed that: